Lifestyle guide for the modern yogi

LATEST

YOGA

LIFESTYLE

HEALTH

LATEST

Best way to start Yoga at home

Starting a yoga practice at home offers the flexibility and affordability to enjoy numerous classes...

Best Yoga pants – Our top 11 Yogi outfit clothing selection 2025

Whether you’re a seasoned yogi or just starting on your yoga journey, finding the right...

Yoga statistics 2025: trends, participation, and growth

As a yoga teacher and long-time practitioner, I’ve experienced the incredible diversity of yoga firsthand....

Schizophrenia: a spiritual gift or mental illness?

Is schizophrenia a gift?Is schizophrenia a gift? For years, mental health professionals and spiritual practitioners...

Healing through trauma-informed Breathwork

Why Breathwork matters in trauma recoveryHealing from trauma can feel like trying to untangle a...

Hot nude yoga hawaii review: Aaron Star’s body-positive practice now streaming

“It’s not about perfection. It’s about permission.”Okay, so full confession: when I first heard about...

Bakasana and Parsva Bakasana (Crow and Side Crow)

Flying low before you soarThe first time I tried crow pose, I face-planted. Hard. But...

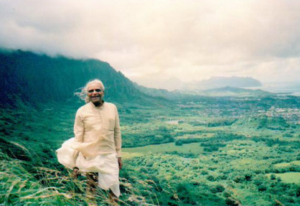

B.K.S. Iyengar: The man who brought Yoga to the West

His enduring influence on Western YogaB.K.S. Iyengar was not just a teacher of yoga—he was...

Pilates vs Yoga — What’s the real difference?

What’s the real difference between Yoga and Pilates?Let’s be honest—Yoga vs Pilates is a bit...

13 Benefits of headstand: why standing upside down is good for your body & brain

Some see the yoga headstand as a powerful pose. Others see it as a risk...

Bhakti Yoga meaning: devotion & spirituality explained

What is Bhakti Yoga?Honestly, the first time I heard the words “Bhakti Yoga,” my brain...

What is spiritual manifestation?

Manifesting a blue teapot (without even realizing it)A few years ago, I put a blue...

How to teach Yoga online

How to teach Yoga online? This will cover everything you need to know – from...