Penjor: what does it represent in Balinese culture?

After living in Bali for more than 17 years, there are certain moments when the island feels unmistakably sacred. One of those moments arrives when penjor begin to appear along the streets.

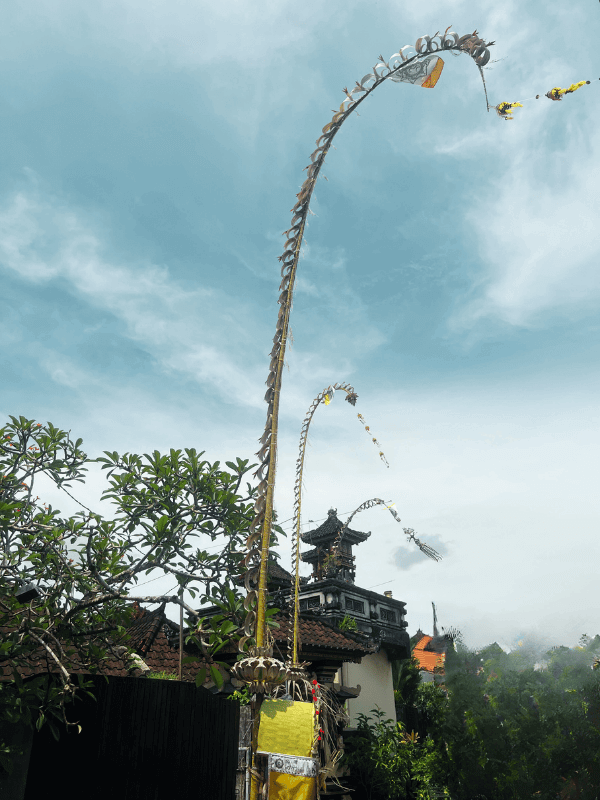

Overnight, familiar roads transform into ceremonial pathways, lined with tall, curved bamboo poles adorned with coconut leaves, fruit, rice, and intricate handwoven ornaments.

You will most often see penjor during major Hindu festivals such as Galungan and Kuningan, though they also appear during important temple anniversaries and village ceremonies.

To outsiders they may look decorative, but to Balinese Hindus, penjor carry layered spiritual meaning that reflects balance, gratitude, and the relationship between humans, nature, and the divine.

What is a Penjor?

A penjor is a tall bamboo pole, carefully selected and bent into a graceful curve. It is traditionally placed at the entrance of a family compound, temple, business, or community space. The word penjor comes from the Balinese word unjor, meaning to bend or arch.

While decorative versions exist today, ceremonial penjor are offerings. They are created using natural materials only and assembled according to long‑held customs passed down through families and villages.

The spiritual meaning behind Penjor

At its core, the penjor represents dharma overcoming adharma, the eternal balance between good and evil. This same philosophy underpins major Balinese ceremonies, including the Galungan festival, when ancestral spirits are believed to return to the earthly realm.

In ancient Balinese manuscripts, including those attributed to Sri Jaya Kasunu, the penjor is described as a symbolic mountain.

In Bali, this mountain is Mount Agung, the most sacred peak on the island and the spiritual axis of the universe. The penjor’s vertical form connects earth and sky, while its curve mirrors the flow of life from the divine down to humanity.

Many Balinese also interpret the penjor as a manifestation of the naga, sacred serpent deities associated with water, fertility, and protection. In this interpretation, the base of the penjor represents the naga’s head, while the curved tip forms its tail, arching protectively over the household below.

The elements of a ceremonial penjor

Every part of a traditional penjor carries meaning. Nothing is placed randomly.

Fruits and crops that grow above ground, known as pala gantung, symbolize abundance and divine gifts. Root vegetables, or pala bungkah, represent grounding, strength, and sustenance. Grains such as rice, referred to as pala wija, stand for fertility and continuity of life.

Woven palm decorations and cakes are added as offerings, and near the tip hangs a sampian, a floral ornament crafted from coconut or palm leaves. Together, these elements express gratitude for nature’s generosity and acknowledge the gods and ancestors who sustain it.

Making and placing a Penjor

Traditionally, penjor are made by families and community members in the days leading up to Galungan. The process takes time and skill. Choosing the right bamboo is essential, as it must be strong enough to bend without breaking.

In modern Bali, many families purchase pre‑made penjor due to time constraints.

While this has become common, there has also been a renewed effort in recent years to return to older styles using exclusively natural materials, avoiding plastic or synthetic decorations.

On the eve of Galungan, men and boys raise the penjor at the entrance of the home. By morning, the streets are transformed, creating a ceremonial corridor for ancestral spirits returning to visit their families before their departure on Kuningan, the final day of the festival cycle.

Ceremonial Penjor vs decorative Penjor

Not all penjor are sacred. Decorative penjor are often used for business openings, festivals, or aesthetic displays. These may include nontraditional materials and do not follow ceremonial rules.

Ceremonial penjor, by contrast, are offerings. Sacred ornaments and materials are used with intention, and their purpose is spiritual rather than visual. Understanding this distinction is important, especially for visitors who may encounter penjor outside religious contexts.

Penjor and daily spiritual life in Bali

What makes penjor so powerful is that they are not confined to temples. They stand at doorways, along streets, and in everyday spaces, reminding people to live according to dharma.

This same philosophy is echoed in other Balinese rituals, such as Melukat water purification ceremonies, where balance is restored through cleansing, and in sacred performances like the Barong dance, which dramatizes the struggle between protective forces and chaos.

Around Nyepi, the Balinese New Year, villages prepare massive Ogoh-Ogoh statues to represent negativity and evil before ritually destroying them, a powerful reminder of the island’s spiritual commitment to restoring harmony.

Why Penjor still matter today

Despite modern development and tourism, penjor remain one of the clearest expressions of Balinese identity. They are reminders that spiritual life here is not separate from daily life. It is woven into streets, homes, food, and community relationships.

After nearly two decades in Bali, seeing penjor rise before Galungan still signals a shift in energy. The island slows down. People return home. Attention turns inward. And for a brief period, the world feels aligned again.

Final thoughts

Penjor are far more than decorative bamboo poles. They are living symbols of gratitude, balance, humility, and connection to the divine.

Whether standing tall in a busy town like Ubud or gently swaying in a remote village, each penjor carries the same quiet message: live with awareness, honor your roots, and walk the path of dharma.

If you find yourself in Bali during Galungan or Kuningan, take a moment to stop beneath the arch of a penjor. Look up. And remember that in Balinese culture, beauty is never separate from meaning.

For more info on Bali’s best spots for the modern yogi

| STAY | SPA | PLAY | EAT | SHOP | YOGA |

Download our ULTIMATE BALI GUIDE for free.