yoga for life – the yoga sutras of patanjali

quality sattva – clarity & joy

The secret to mastering any new skill, concept or behavior, according to my teacher’s teacher’s teacher, Yoga master T. Krishnamacharya, is repeating and digesting so as to become comfortable, or ksema. So before we move on, let’s look back.

In previous articles, we saw that ‘yoga’ is a common Sanskrit word with many meanings, including ‘to link.’ The word ‘yoga’ however, is distinct from Yoga, one of six formal philosophies, or darsanas extracted from the ancient Indian Vedas.

The aim of Yoga darsana, a cohesive healing art fully articulated in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, is to reduce human suffering by transforming the mind. We saw that yoga’s view of reality is linked to Samkhya, a dualistic philosophy– also derived from the Vedas.

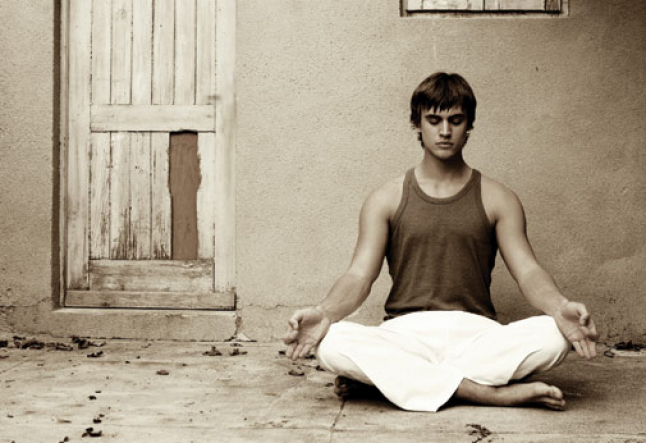

According to Samkhya, the first element is purusa, the formless seer. Pure spirit, purusa, is ever unchanging and is characterized by truth, clarity, and joy.

The second element is matter, prakriti, which includes all of nature and the mind. The essence of prakriti, of the material world, is changing.

Samkhya describes matter’s three distinct rates or qualities of change: rajas is the agitated, quick-like-fire quality, tamas is the slow, dully resistant-as-a-rock quality, and sattva is the luminous change: always balanced, appropriate, and sustainable.

Because Samkhya is based in dualism, prakriti and purusa are seen as connected, yet still separate.

The deepest connection of these elemental forces is through the quality of sattva. When this quality predominates, the world of matter becomes closer to the world of spirit.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras – yoga’s foundational text – is, in simple terms, an instruction manual for creating a satvic life. We also learned that purusa, consciousness, is the source of limitless wisdom and insight, and the basis of our core values. It is a guiding light which, when followed, always leads to a better life and greater joys.

Meanwhile the mind, in an attempt to create stability amidst prakriti’s constant change, is constantly forming habits, or samskaras. Problems arise, according to yoga, because purusa can only perceive the world through the conditioned mind. When the mind imposes past mental patterns on present time events, our perception is distorted and our behavior inappropriate to the challenge at hand.

This inevitably leads to suffering and sadness. So, while many still think of yoga as a simple exercise regimen, we have seen that this subtle spiritual psychology was traditionally used to refine mental habits. This helps us to achieve, with greater ease, any goal, gross or subtle, great or small. That’s the good news. Yoga’s bright promise, however, comes with a condition: we must practice.

You mean I have to do something?

From the very First Sutra, 1:1, yoga is introduced as ‘anu asasanam’, ‘following directions which leads to a new experience.’ Not merely an academic study of interesting ideas, yoga is, by definition, taking action. To feel something different, we must do something different.

To be more, we must do more.

Sutra 1:12 reveals the way to more. Yoga’s definitive tool for self-improvement, for achieving our goals, is practice. Regular practice, or abhyasa, is the first of two essential steps toward positive change.

The second is vairagya, the ability to detach, to let go of the negative. Abhyasa and viragya are like the two wings of a bird. To arrive at a new destination, both are required. This sutra also suggests a simple strategy: that we should always add something positive before attempting to give up the negative, that abhyasa precedes vairagya.

For it is much easier to let go of a bad habit or limiting belief after we have replaced it with something better. The new pattern provides the strength and stability to release the old, and focusing on the new prevents us from dwelling on the loss of the familiar.

The next sutra, 1:13, explains that every practice should be carefully designed to achieve a specific goal. The Yoga Sutras never insist on a specific goal, but explain that whatever the goal, the correct practice is required to obtain the desired result. If the student’s goal were to reduce the stress caused by being self-destructive and overachieving, the correct practice would probably be one that is more gentle and kind.

A practitioner eager to heal a physical injury might need to forego postures altogether in favor of breath work or visualization.

The number of goals and the practices needed to achieve them are infinite. Clearly, vinyasa krama, or individualized course planning (with the aid of a qualified teacher) is crucial. Owning new habits. Sutra 1:14 describes the very mechanics of learning, the dynamics of habituation.

According to Patanjali, the abhyasa will be most effective when the practice is repeated:

1) Continuously over time,

2) Without interruption,

3) With belief that it will work, and

4) With enthusiasm.

Only through faithful repetition can the foreign become familiar, the impossible, possible. This fits with Yoga’s definition as ‘the ability to do today what we could not do yesterday, to do tomorrow what we cannot do today.’ Moreover, Yoga teaches that consistent, enthusiastic practice makes the impossible possible in several specific areas of life.

Commonly known as the eight limbs, or ashtanga, they are listed from gross to subtle, from outer to inner. They are: relationship, lifestyle, body, breath, senses, and mind (three are about the mind).

While the Yoga Sutras are rich with wisdom and insight, the eight limbs are the true yoga sadhana, ‘that which can be practiced, that which can be done’.

What is a practice? For the average modern student, yoga practice may consist of one to six group asana classes per week, or performing a prescribed sequence of postures at home, or, perhaps, following along with a guided workout video. While this can be enjoyable and has yielded positive results in the west for the last 40 years, it is worlds apart from yoga’s first 2,000 years.

Fortunately, there are still some contemporary lineages (the one in which I practice, for instance) that still offer yoga in the traditional manner. Traditionally, a practice began with a student having the humility to admit to himself or herself (and later to a teacher) that he or she needed help.

This led to serious searching and ultimately finding the right teacher. (Serious searching is when the intention is ultimately to choose one teacher, rather than endless shopping for shopping’s sake) If the teacher accepted the student, they would begin a relationship.

Then, they would meet regularly, always one on one. (Children were taught in groups.) Using the Yoga Sutras as a guide, the student and teacher would explore various strategies to help make the student’s mind more sattvic and improve his or her life. Working the limbs.

First, the teacher might suggest practical methods for integrating more honesty and kindness (yamas) into the student’s personal relationships.

If necessary, the teacher would help find ways to clean up, simplify and refine the student’s lifestyle (niyamas). To make the student’s body strong, light and flexible, appropriate postures (asana) were selected, adapted and sequenced. Lengthy, arduous practices emphasizing perfect posture were taught primarily to children.

Adult students, fully occupied with the day’s activities, were prescribed just enough asana to help them fulfill their responsibilities and enjoy their lives. Though better posture signified improvement for children, the true measure of success with adults was richer, more satisfying relationships.

Because of the strong link between breath, mind, and emotions, breathing techniques (pranayama), designed to make the breath long and smooth, were a central feature in mature yoga practice. Classical teachings suggested as many as four pranayama practices per day.

To refine the student’s sensory diet, further lifestyle changes were suggested. Sounds, mantras and chants were carefully chosen for both their physiological effects and their meaning. Sound, correctly applied, is a powerful addition to any practice, as it lengthens the exhale, focuses the mind, and stabilizes the emotions.

Also, sitting quietly for some time was often added to the practice. Reaping the benefits. Integrating these various elements in a daily personal practice shifts the student’s focus from outside stimuli to a more inward (pratyahara) phenomenon, such as one’s own memories, values, sensations, dreams, and goals. Interestingly, this inward shift is a major factor in improving the student’s outward relationships.

Over time, the effects of regular practice are profound, transforming the practitioner’s world from the inside out and the mind from the outside in. Meditation, the ability to focus on a chosen object or in a chosen direction, is both the result of other practices and a practice unto itself.

Gradually, an inner light shines through, and problems are replaced with clarity, joy, and boundless enthusiasm. This is yoga in full flower, a truly universal, yet highly individualized celebration of life in all its changing forms.

To Depart

To reap the marvelous benefits of yoga, one needs only to find his or her teacher and begin practicing. Through correct practice with the right teacher, we will surely find what we’re looking for.