why is a “happily ever after” ending often a must in mainstream movies?

Everyone, to one degree or another, is familiar with tragedy. In fact, for many on a spiritual path, it was the rough seas of adversity that placed them on that path in the first place. Going through tough times may be grueling, but as the ancient Greeks were well aware, watching others go through them is downright entertaining. So if this is the case, why does Hollywood continually shy away from making films with tragic undertones? Why is a “happily ever after” ending often a must in mainstream movies?

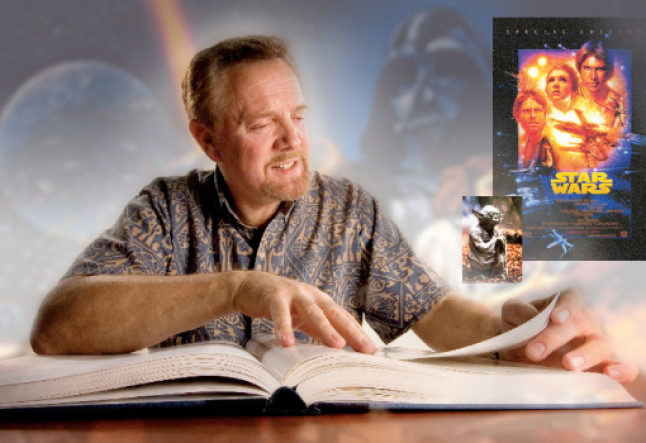

Someone who has spent a great deal of time pondering this question is Dr. Jonathan Young, founder of the Center for Story and Symbol. “The tragic thread is the part that touches us most deeply,” says Young, who is a psychologist, and who assisted famed mythologist Joseph Campbell for many years before becoming the Founding Curator of the Joseph Campbell Archives and Library. Young observes, “The healing and wisdom that comes from watching things unfold in a disastrous direction is good for us because it humbles us.”

Being humbled may not be on the top of our daily “to do” lists, but according to Aristotle, tragedy supplies us with the opportunity for catharsis, a form of emotional cleansing and relief that audiences in Greece would feel when watching people on stage suffer fates much worse than their own. Hollywood may love a good fairy tale, but one only has to go back and read the original Brothers Grimm collection to find that they’re populated with more witches than singing birds.

In the 1970s, the era that brought us Watergate and a swelling crisis in Vietnam, one only had to pick up a newspaper to be humbled on a daily basis. During what many still consider the pinnacle of great filmmaking in Hollywood, art began to imitate life as the “Movie Brat” directors of Hollywood New Wave filled the theatres with dark, gritty character dramas. The anti-heroes of such films as Taxi Driver, Chinatown and One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest reflected the moral ambiguity of the zeitgeist in a way that had not been seen before. Realism reigned, and then Star Wars came along.

“Star Wars brought kids back into the theatre,” says Young. This is to say nothing of the millions of grown up kids who also showed up. From the moment the fairy tale-like crawl, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away,” flashed on the screen, George Lucas took audiences out of reality and into the realm of fantasy. Modeled after Joseph Campbell’s blueprint for the Hero’s Journey with a heavy basis in myth and archetype, the film tapped into audiences’ collective core, with box office grosses to prove it. According to Forbes, the film franchise has gone on to gross nearly $20 billion over the course of its twenty-eight-year history.

The shift from smaller, intimate films to crowd-pleasing blockbusters like Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark wasn’t surprising. According to Young, “if too much dramatic change happens collectively, people get anxious and there’s a conservative swing, resulting in a lot of safe art for a while.”

That’s not to say that Star Wars was safe – but with its mythic overtones and fantastical setting, it was a perfect form of escapism for audiences who had just lived through very troubled times. It is however interesting to note, adds Young, that the prequel trilogy that appeared years later was indeed a tragedy. “Lucas was courageous and generous enough to use the most valuable film franchise in history to tell a tragic story.”

One either has to be incredibly rich, like Lucas or Mel Gibson, or incredibly poor, like 99% of the filmmakers at Sundance, to make a movie with tragic undertones. Stories abound in Hollywood about how studios engage in bidding wars for the film rights to books or true stories, only then to whitewash them and change the endings so that they’re less ambiguous and more uplifting. “Most Hollywood films end on an upbeat note, even if there have been terrible injustices and afflictions in the story,” explains Young. “Because we live in a ”˜grief-denying culture,’ films that deal with loss often cheat at the end and suggest a level of closure that is not realistic.

Still, psychologically, we crave pathos. “People find tragic stories comforting, because they have already accepted that adversity is not a mistake. It is a normal part of everyday life. People who accept the tragic aspects of the journey tend to be more contented. They have fewer rude surprises,” Young says.

One glance at the Foreign Films aisle at your local video store proves that filmmakers from other countries aren’t afraid of tragedy – so why is Hollywood? Because, says Young, “America values effectiveness. We’re terrific problem solvers. Because of our strong practical emphasis, we’re often able to find solutions where others have failed. The dark side of this is a tendency to see all ailments as curable. Tragic literature and film deals with situations that cannot be fixed.”

As each year’s Sundance lineup attests, American filmmakers are still making movies in the vein of those 1970s classics – but most of the time they’re smaller, independent films with limited distribution. However, each year we can count on at least a few bigger budget films being made that get around the “happily ever after” barrier – and then go on to be celebrated during awards season, such as this year’s Oscar-nominated films Brokeback Mountain, Crash, Capote, Munich and Good Night, and Good Luck. Yet, according to the Los Angeles Times, every one of them except for Munich were funded partly or completely by non-studio investors. None are huge hits at the box office.

It may be disconcerting to hear that Crash has only grossed a total of $53.4 million while Big Mama’s House 2 made $28 million during its opening weekend, but according to Young, that’s normal. “There’s a number of tribes in a culture,” he explains. “And some are watching the really challenging, transformational films all the time…and some are watching the popcorn movies.”

The Center for Story and Symbol, folkstory.com

Read next >> Jill Culver