freedom from addiction

The Recovery Sutras : Yoga – Habit & Freedom from Addiction

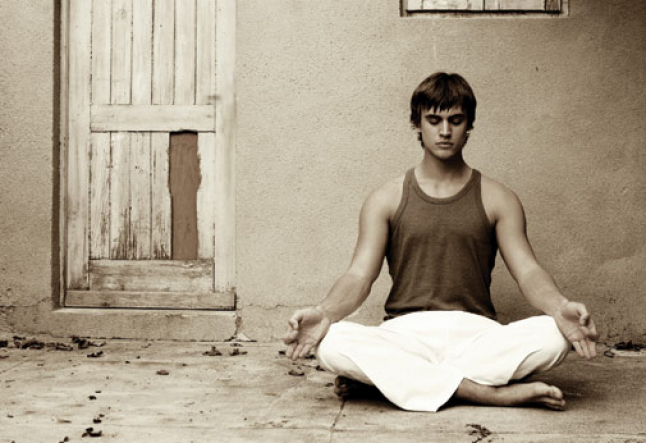

The path toward freedom from addiction can be challenging, but incorporating yoga’s healing power can provide a much-needed support system. In this article, we delve into the use of classic yoga models to overcome addiction and its effects.

From exploring the root causes to discovering effective healing techniques, the aim is to empower individuals on their journey to reclaim their lives.

Use the table of content to get to the section of the article that interests you most.

Table of contents

Discomfort du Jour

Addiction has been called “a plague,” “a modern scourge” and “the disease of our era.” Statistics show that at least one in ten Americans are currently addicted to alcohol or drugs (prescription or otherwise), and that every addict-alcoholic negatively impacts at least 10 people.

Whatever else these numbers indicate (volumes, actually), it is quite clear that the tendency to become dependent on substances such as drugs and alcohol, and processes like shopping and sex, is a pervasive human characteristic which has adversely affected millions worldwide. Yoga, correctly understood and practiced, can help.

Addition Defined

“Continued use of a substance (or behavior) despite increasingly negative consequences” is one accepted definition of addiction. Another—my personal favorite— is “wanting the wrong thing very badly.”

The 12-step program defines alcoholism (essentially identical to addiction) as “a physical allergy coupled with a mental obsession linked to a spiritual malady,” thus qualifying alcoholism-addiction as, perhaps, the first truly holistic disease.

Yoga explains addiction as the mind’s innate tendency to mechanically and habitually respond to present-time challenges with behaviors that worked in the past (samskaras). In other words, today’s problems were once yesterday’s solutions.

Yoga Redefined

Far from its current incarnation as a group stretch class (now with music), yoga is originally one of six classical Darsanas (philosophies) derived from the ancient Indian Vedas. In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, yoga’s source text, yoga is outlined as a practical spiritual psychology.

In this sophisticated self-care system, the intimate student-teacher relationship provides the rich context for developing unique strategies and practices that ultimately lead the individual to profound personal transformation. (As one who studies and teaches from this traditional model, I am perpetually amazed at yoga’s immense power to heal disease and change lives.)

In Another Dimension

Yoga presents the human system as an ever-evolving matrix of five interconnected dimensions, or mayas, each of which affects and is affected by the others. (Though some early influential commentaries inaccurately referred to the levels as koshas, literally “bags,” the Taittiriya Upanishad, the actual source text, describes these interrelated components more appropriately as mayas, or “that which extends throughout.”)

The Five Mayas progress from gross to subtle, beginning with the physical body, or anna-maya. The second Maya, the energy or prana-maya level, is linked to breathing and the physiological functions.

Next, we find the senses and outer mind, or mano-maya, followed by the deeper mind, the values-shaping vijnana-maya level. Finally, at the deepest heart of the person is the emotional level, the ananda-maya, expressed as the inherent potential to experience a lifetime of sustained joy.

Yoga uses the Five Mayas model to understand and treat health and disease holistically. Thus, a physical problem might have its roots in the mind, an emotional trauma could affect digestion or other physiological functions, and behavior that conflicts with our core values could negatively affect our emotional state, the regularity of our heartbeat, and the shape of our spine.

In later articles, we will explore yoga’s various tools for treating the mayas, including asana for the physical body, pranayama and chanting for the prana-maya, meditative tools for the mental levels, and the loving support of a kind, honest teacher as a primary tool for cultivating positive, flowing emotions.

How to Heal

In addition to the mayas model, yoga offers a precise four-part methodology for creating and improving health. Clearly outlined in the Sutras’ second chapter, yoga’s healing strategy requires that we identify the symptoms (heyam), discover the cause (hetu), establish a goal (hanam), and choose the best tools to achieve the desired results (upayam).

This simple model works whether the problem presents as primarily physical, physiological, mental, emotional, or in the case of addiction, a combination.

Let’s begin to examine the heyam of addiction related to the Five Mayas.

Houston, We Have Heyam

At the anna-maya level, the physical effects of long-term abuse include damage to the heart, lungs, stomach, liver and kidneys, as well as structural degradation, such as osteonecrosis, in which there is skeletal deterioration. Furthermore, addicts in the acute stages of withdrawal experience nausea, vomiting, tremors, aches, fever and seizures, depending on the specifics of the addiction.

At the prana-maya level, all addictive substances distort natural, healthy breathing, which according to Yoga Sutra II:50, is long (dirgha) and smooth (suskma). Depressants such as alcohol and heroin make the breathing slow and shallow, while stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine induce breathing that is rapid and irregular.

Compromised breathing impairs circulation, digestion, elimination, communication and many other physiological functions. In addition, substances that are snorted or smoked, such as marijuana, cigarettes and cocaine, can aggravate and ultimately destroy the sensitive organs of respiration.

Related Course >>> Life Beyond Addiction Programs by Tomy Rosen

As the Eastern model considers the lungs, rather than the heart, the body’s central pump, many of yoga’s tools, including asana (done properly), pranayama, chanting and the like, are aimed at making the breath slow and deep.

Conversely, anything that distorts the breathing, such as stress, obesity or drugs, is clearly life-diminishing and should be reduced, replaced or avoided altogether. This includes the widespread and damaging habit of holding the breath while performing various yoga postures (asanacide).

Nowhere But Up

At first glance, the phenomenon of addiction seems a bleak obstacle to the sustained joy (paramandana) that is, according to yoga, our birthright.

For many, however, hitting bottom is a springboard to an exceptional new life, one in which the sorrows and loss of addiction serve as an opportunity for transcendence and growth. For these lucky addicts, the desolation of addiction provides a stark reminder of the mind’s limitations, while simultaneously creating an energizing thirst for what lies beyond it.

In yoga philosophy, that which exists beyond the mind is called purusa, the unchanging, individual consciousness at the core of all living things. This formless spirit, a true higher power, is the essence of freedom and the limitless source of all confidence, wisdom and joy.

In part two, we will explore the remaining three mayas and the complex relationship between the mind, emotions and addiction by examining the addictive cycle—the downward spiral from occasional user to full-blown addict.

Understanding addiction’s subtle symptoms

Addiction is a modern epidemic that has taken thousands of lives and diminished countless more worldwide. In the first part of this ongoing series, addiction was defined as being “the continued use of a substance (or behavior)—alcohol, drugs or food, or other processes such as gambling, shopping or sex—despite the increasing negative consequences to the individual’s health, mental state or social life.”

Twelve-step programs explain alcoholism, akin to addiction, as being, “a physical allergy linked to a mental obsession rooted in a spiritual malady.” Together, the addiction/alcoholism paradigm can be explained as the first truly holistic disease.

We looked beyond yoga’s current form and uncovered its deeper essence as a spiritual psychology that offers an intimate student-teacher relationship along with a multi-faceted personal practice, replete with tools for healing and transformation.

A regular yoga practice can dramatically improve the lives of those who suffer from addiction by helping reduce symptoms and reverse the causes.

The Power to Change

Yoga’s sister philosophy, Samkhya, posits a formless consciousness at the core of each individual as the foundation for all positive change. When conditions are sattvic, or “right,” this unchanging seer, or cit, imbues our lives with abundant confidence, wisdom, and joy. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, yoga’s foundation text, is a guidebook for cultivating more sattvic conditions.

Yoga perceives the human system as five interconnected, interactive dimensions, or mayas. The first layer is the overall physical body, or annamaya—the level to which the entirety of Western medicine is confined. As we look deeper, we find the breath body, or pranamaya, which guides our physiological functions.

The next level is the manomaya, or mental layer, which incorporates the senses, processes information and incites behavior.

Then we have the vijnanamaya, or the conditioned mind, which is home to our preferences and values. Lastly and closest to the core is the anandamaya, or emotional body, representing our inherent potential for a lifetime of sustained joy.

Using yoga’s methodology for healing, there are four specific steps you can follow that will help guide you on this quest for healing and change. The first key begins with observing the symptoms, or heyam. Next, you must discover the cause or hetu; then set specific goals for change, or hanam.

Finally, these measures can by met by implementing the proper tools, or upayam. This classic therapeutic model is highly effective regardless of whether the problem presents itself as a physical, mental or emotional one or in the case of addiction, as a combination of them all.

The Downward Spiral

While addiction creates negative symptoms at every level, the deepest problems exist in the subtle levels of the mind. We can identify these levels as the mano, vijnana and ananda mayas. We can better understand these effects by examining the disease’s progression, commonly referred to as the “addictive cycle.”

The cycle begins when an individual is exposed to negative mental patterns and behaviors through their parents, teacher or peers. Violence, dishonesty or severe, prolonged criticism can all contribute to the accumulation of negative patterns of thinking.

The accumulation of this type of negativity creates uncomfortable emotions such as anger, shame, and guilt, as well as a general feeling of discontentment with self.

Once someone becomes conditioned with this negative pattern of thinking and then ingests alcohol, drugs or a combination of both, they usually experience instant bliss—a sudden transcendence from their usual state of being. As most addicts will attest, indulging in the substance or activity was an initial, euphoric relief from years of conscious or unconscious suffering.

Since these individuals usually lack the necessary insight or support for any acknowledgment or resolve of their issues, the temporary freedom from negative thoughts and emotions is a powerful incentive to indulge. Over time this pattern will repeat itself with greater frequency and intensity.

It Just Gets Worse

Prolonged use and abuse lead to a lifestyle that is increasingly addiction-centered. The individual often feels guilty about their behavior and will attempt to hide their habit from those closest to them.

As the addiction escalates, behavior becomes more erratic until friends, family, and co-workers eventually begin to express their concern and discontent.

Unfortunately, the addict usually responds to their heartfelt appeals with powerful defense mechanisms fueled by denial, delusionality, and rationalization—intrinsic aspects of the addictive cycle.

At this point, the addict is incapable of processing negative feedback or modifying their behavior in any sustainable way. Periodic abstinence is evidence only of the addict’s ability to temporarily or intermittently exhibit control over their behavior and is not a sign of progress; it is merely another confounding characteristic of the addictive cycle.

As irresponsible behavior and dishonesty increase, so do feelings of shame and guilt.

Over time life conditions worsen and the individual becomes more isolated, angry and hopeless. Simultaneously, the addict develops a tolerance and eventually needs more of the substance or activity in order to feel the same comfort and joy. At this point, the cycle is complete. The individual has degenerated from user to abuser to full-blown addict.

Fool Yourself

Addiction manifests in the manomaya as severe mental mismanagement. The addict’s ability to learn and grow from life experiences is profoundly diminished by the mechanisms of denial, delusionality, and rationalization. Perhaps you have used or heard one or all of these excuses.

Denial is defined as, “rejecting the facts despite clear evidence of their veracity.” This includes denying the fact entirely with such rationalizations as, “I didn’t get fired because of my drinking, the company was just downsizing.” Minimizing the seriousness of a given situation is a common form of denial.

Check Out>>> Life Beyond Addiction Programs by Tomy Rosen

Being delusional is a condition in which the individual clings, with absolute certainty, to beliefs based on false evidence or no evidence at all. “Okay, so I failed at quitting pot ten times so far. This time I’m sure I can do it.” Twelve-step programs refer to this as the definition of insanity, “doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”ƒcheck

Finally, rationalization can be defined as, “providing false motivation for an action.” Rationalization can be characterized by absurdities like, “It’s not an addiction, I just throw up so I don’t get sleepy at work.” These defenses highlight the basic deception and dishonesty that fuel the addictive cycle.

Fountain of Sorrow

The Yoga Sutras label these tendencies collectively as avidya, or “misperception.” Sutra II:5 defines avidya as, “mistaking the impermanent for the permanent, the unclean for the clean, the painful for the pleasurable and the unconscious for the conscious.”

This aptly describes the full-blown addict, who literally dies trying to sustain an intrinsically impermanent high, who embraces and defends habits and attitudes that are physically, mentally and emotionally toxic, who confuses the ever-increasing pain of addiction for pleasure and who continually misperceives their habitual, unconscious indulgences as a conscious choice.

Avidya is a central concept in yoga. According to Patanjali, misperception is the root cause of all human suffering, or duhkha, and the fundamental obstacle, or klesa, to achieving our goals.

The more exaggerated the patterns become in the full-blown addict, the easier it is their avidya and the suffering it creates. But the tendency to misperceive is universal, and the same patterns that haunt and torture the addict will negatively affect us all, at one time or another, throughout our lives.

There and Back

Like a photo enlarged for improved viewing, the addict’s life-and-death struggles and salvation are an easy-to-read roadmap for our own personal challenges and their possible resolution.

If a hopelessly strung-out junkie or liver-diseased alcoholic can return from the depths of despair to a life brimming with hope and gratitude (as frequently happens in twelve-step programs), then surely the rest of us can overcome our worst habits and find our way back into the light.

To the extent that we allow ourselves to be inspired by the addict’s journey, it becomes obvious that our greatest suffering and most grievous errors can serve not as a source of shame but as a beacon guiding others back to the clarity and joy that is our true nature, the reason we all came to be.

Living the lie – addiction and confused values

Treatment at the drug rehabilitation center where I teach costs nearly $1000 a day. The minimum stay is sixty days and health insurance is not accepted. You won’t find any street kids or drug-pushing junkies there. Rather, among those fidgeting through group therapy, unraveling tangled lives, detoxifying and practicing yoga are the mothers, fathers, sons and daughters of our nation’s finest families.

One word that often comes up during group sessions is enviable as in, “I don’t know how I became an addict; I had such an enviable life.” This particular choice of words belongs to the next level of yoga’s Five Mayas model (explained in part two of the recovery sutras) the vijnana or personality and maya, the dimension of personal values.

Not My Beautiful House

Those well-heeled (not to be confused with well-healed) addicts were indeed living enviable lives. Surely they were good lives full of things that should make someone happy.

Unfortunately, these people were leading lives according to someone else’s values; they were leading lives they felt they ought to love rather than lives they actually did love. In the field of addiction this is known as characterological conflict, the gap between an individual’s core beliefs and their actual behavior.

Twelve-step meetings are rife with people who used to drink or use drugs because they were uncomfortable in their own skin. They used because they felt like outsiders walking through someone else’s life, disconnected from their friends, family and their careers.

The need to create a life that is aligned with our core values is addressed in the Yoga Sutras’ description of meditation, the essence of yoga itself.

More Than a Side Stretch

Sutra 1:2 defines yoga as the ability to direct one’s attention on a chosen object and sustain it without wavering. This single-minded focus quiets the mind and allows for the experience of samadhi or absorption, an emotionally rich connection between our innermost self and the chosen object of attention.

Now this suggests far more than just staring at a candle. Whatever object we choose to focus on, grow closer to and absorb will ultimately define our values, shape our character and determine the quality of our lives. Someone who claims to value helping the poor should actually be giving sustained attention, on a daily basis, to see that those in need do in fact get help. This action will in turn influence the personality of the person giving the attention.

Claiming to value something but not giving it full attention is the exact opposite of yoga. According to the sutras, this divided attention often reflects a superficial, unstable mind and cloudy or conflicting values. Sadly, this condition is increasingly common in a world offering more and more shiny objects, easy promises and diminishing accountability.

What Makes Me

We are exposed to conflict and other opposing conditions from the moment we are born. According to yoga, our core consciousness or cit always knows what’s best for us. This unbiased observer manifests itself in our ability to make wise choices when presented with a full spectrum of possibilities.

By using our emotions as a gauge, this innate intelligence will guide us towards joy and other positive outcomes and will steer us away from choices that might result in suffering or other negative emotions.

When exposed to opposing conditions, we will naturally choose kindness over cruelty and honesty over dishonesty. If presented with the choice of a challenging job that pays little or doing something we love which pays well, we will likely choose the latter. Eventually these interconnecting preferences coalesce and form the vijnana maya, home to our personality and our values system.

Choosing to Smile

Once this values system has been established, whenever we align our choices and behaviors with our core values, we will experience more joy. Conversely, when our behavior is in conflict with our values or when our values conflict with each other, (“I want money but I don’t think I should want money.” Or, “I love sex but I think it’s wrong.”) we will experience suffering.

Twelve-step programs describe this discomfort as being restless, irritable and discontent. Yoga uses the Sanskrit word duhkha meaning, “feelings of constraint or limitation.” By any name, the state of conflicted values is a precondition for the development of full-blown addiction.

The greatest potential for addictive behavior exists whenever we are living a lie, conforming to another’s expectations or struggling with the notion that it’s not okay to want what we want—a notion usually instilled by conflicted parents, hypocritical religious figures, politicians and other liars.

Check Out>>> Life Beyond Addiction Programs by Tomy Rosen

Why We Use

Deeply uncomfortable feelings demand release. This release can be easily obtained, at least initially, by indulging in an “addiction of choice.” It is when the seeking of such relief becomes obsessive that we find ourselves at odds with our core values. This cyclical, progressively deepening behavior leads to the disease of addiction.

Both the Yoga Sutras and The Big Book agree that samyama or long-term sobriety, is contingent on clarifying values either through meditation or by practicing the twelve steps, and by living a life of integrity and rigorous honesty.

For it is only when we are consistently able to choose, focus and sustain our attention on the elements that produce lasting joy, that we can fully flourish and be free of unhealthy patterns, habits and addiction. That would be enviable!

Healing the emotional body – the goal of all goals

The aim of yoga and in the universal pursuit in life is expressed by the Sanskrit word paramananda, or more sustained joy. For whatever we see as the goal of our existence, we ultimately choose to associate ourselves with only that which we believe will lead to paramananda.

Whether it is money, fame, family, service, union with God, enlightenment or a stable mind, each is valued only as much as they are equated with an increased feeling of lasting joy. In the end, whatever our personal situation or philosophical orientation, paramananda is the quality all goals aspire to achieve.

According to yoga’s holistic anatomy, The Five Mayas, the dimension that manifests the potential for more sustained joy is the ananda-maya, or the emotional body. Because this core component is the most subtle of dimensions, it easily permeates and influences all other aspects of the body. Those who are more joyful tend to stay healthier, heal more quickly, learn more easily and maintain clearer values.

Temperature rising

In studies of addiction, the ananda-maya is described as an emotional thermostat, ranging from the darkest depression on one end of the spectrum to the deepest joy on the other. We each develop an emotional disposition somewhere along the scale.

This emotional temperature is somewhat influenced by genetics and pre-natal conditions, but is primarily shaped by life-experience, specifically our earliest, deepest, most formative relationships. Though the flow of daily experiences will register as being relatively more joyful or depressing given particular circumstances, each individual starts from and returns to their regular set point on the scale.

The condition of our emotional body controls the way we feel about ourselves, other people, fate, God and the state of things in general. It is the unspoken, deeply felt definition of who we are and the way life is.

Someone whose emotional thermostat is set further to the negative side of the scale is more likely to find fault with and maintain resentment toward themselves, others and the situations they face.

On larger issues, they tend to worship a more authoritative, punishing God and can struggle with the notion of a higher power entirely, asking, “How could any God let all of these horrible things happen in the world?”

An individual with an emotional preset that is closer to the joyful end of the spectrum tends to see the positive side of things and is more hopeful and forgiving. Such a person is more easily able to embrace the vision of a gentle, loving God or some other force that supports the universe.

They spread their optimism by encouraging others to reach their fullest potential and engage positive thoughts and behaviors.

Not enough love in the world

In this model, those most likely to develop full-blown addictions have an emotional preset closer to the negative end of the spectrum. Thus, addiction is based upon more than simple genetics or a single traumatic experience.

According to both accepted addiction theory and yoga, the root of the problem lies within the addict’s negative emotional predisposition. It is their fundamental shortage of joy and the result and tendencies toward fear, resentment and sadness, which entices the alcoholic to drink, the addict to use and the overeater to overeat.

The missing link

An essential component in healing the emotional body is the engagement in relationship. Initially shaped through relationships, the emotional body can also be refined through communion with others.

Our relationships offer the opportunity to experience the greatest joys and deepest sorrows in life. Through them, we can move our established emotional set point and change our viewpoint through continuous, positive, long-term relationships that nourish and strengthen our core selves.

The need for healthy, healing relationships also explains why the first of yoga’s eight limbs is named yamas, or relationship. Patanjali offers several sutras to illuminate the guidelines for joyous relationships. In fact, the traditional yoga model prescribed one teacher for each student in order to provide guidance and support through a loving student-mentor relationship.

Though few modern yogis enjoy an in-depth relationship with a teacher, it is a primary component in most Western healing modalities such as the therapist and client relationship in psychology. Without the aid of meaningful personal relationships, yoga, even with all its powerful tools, can only result in relatively superficial change, particularly in those with addictive tendencies. In my own case, for fifteen years, the patterns underlying my addiction such as perfectionism, self-destructiveness and competitiveness in the name of self-improvement were actually deepened through impersonal group yoga classes.

The future of yoga

As an awareness surrounding the importance of relationships has started to grow, more and more yoga teachers are receiving training to offer individualized, relationship-based instruction. Meanwhile, twelve-step programs with their emphasis on sponsorship and intimate sharing continue to offer the powerful, long-term fellowship needed to change the emotional thermostat and heal the emotional body.

Interestingly, even the slightest positive movement on the underlying emotional scale generates an experience so profound it has commonly been referred to as a spiritual awakening. During this spontaneous shift in perception, the individual’s relationships with everyone and everything in their world dramatically evolve. This deeply emotional and life-changing experience is the key element for high-quality, long-term sobriety.

Codependency, addiction’s tarnished mirror

Addiction is a contemporary epidemic which directly affects one in four individuals in America and countless more worldwide. The development of an addictive personality is a result of many factors, but we can begin to understand the influence the family has on addiction by exploring addiction’s natural cohort and its underlying pathology—codependency.

Codependency has been described by various experts as “relationship addiction,” “chronic external referencing,” “addiction to another person and their problems” or “a relationship and its problems.” Symptoms of codependency include difficulty in identifying personal needs, making decisions and verbalizing requests.

Codependents can suffer from negativity, perfectionism and underlying feelings of powerlessness, self-pity or shame.

They have difficulty expressing their feelings and have the persistent need to control, be controlled, satisfy and entertain. It is common for a codependent personality to crave approval and avoid confrontation. Habitual fixers, martyrs, and saviors, codependents are more comfortable helping others than practicing consistent self-care.

Check Out>>> Life Beyond Addiction Programs by Tomy Rosen

If i have it, you may too

To varying degrees, we can find some kind of tendency towards codependent behavior in most people. By and large, we all have a desire to avoid conflict, help others and receive validation, although some of these characteristics can be more intense and problematic in individuals with a propensity for codependent behavior.

Rather than formulate a black and white diagnosis, we best understand codependency as a continuum with increasingly severe and painful symptoms as we approach the far end of the spectrum.

Extreme codependency is a serious disorder and can be life-threatening in certain circumstances. Usually, severe codependency is the result of being raised in a hostile, invalidating or unpredictable environment.

Aggravating factors may be the sudden death of a family member, living within an extreme rule-oriented environment, exposure to religious fanaticism or other forms of abuse and neglect. Emotionally unstable or unavailable parents can instigate the disorder within their children by engaging in rigid, overly competitive or shaming behavior.

Disorder in the family tree

The relationship between addiction and codependency is both subtle and complex. Studies show that individuals become addicted to substances or develop other obsessive, self-destructive behaviors as a direct reaction to either their own or a family member’s codependency. In the lineage of addiction, the addict often marries another codependent.

They produce children who also tend to gravitate toward codependency, addiction or both. These children are likely to marry other codependents and addicts and recreate the cycle for generations. Most addicts, when observing their family history, find no shortage of active alcoholics/addicts, codependents or combinations of the two.

Healing through Yoga

Yoga describes externalized attention as an excess of vital energy (or prana) pushed, pulled or leaked outside the body. According to both yoga and modern addiction theory, this persistent outward focus stems from and deepens the lack of connection with our core self, consciousness.

Twelve step programs use the word “higher power.” Regardless of semantics, this fundamental, habitual misdirection of awareness causes us to become obsessed or addicted to other people, processes, and substances outside of ourselves. Yoga and its root philosophy, samhkya, maintain that incessant outward focus is the basis for all human sorrow.

According to yoga’s timeless teachings, the very source of our being and the limitless confidence, wisdom, and joy it generates exist at the core of each individual; each of us can experience these virtues by continuously focusing our attention in their direction.

Yoga’s central strategy and underlying goal for which its tools are designed is called svadhyaya, or inward focus. Posture (or asana), breath work (or pranayama), visualization, meditation and chanting all serve as methods to interiorize our attention.

A new road home

The “Yoga Sutras of Patanjali,” yoga’s source text, is a detailed guidebook, a how-to manual for the focusing of awareness on a chosen object or in a chosen direction. According to the sutras, the systematic shift of attention inward should be correctly adapted for each individual and practiced with consistency, conviction and enthusiasm over the course of many years.

Through regular practice, the curse of codependency and the spell of addiction can be broken. Whether it is through long-term sobriety (or kaivalya), freedom (or paramananda), or perpetual and long-enduring joy, we can ultimately break the cycle of codependency and addiction. This inner evolution offers the sweet taste of true self-awareness to recovering addicts and offers hope to future generations.

Envisioning a lovable future

In the 1930s, two former alcoholics, Bill Wilson and Dr. Bob Smith spearheaded a grass-roots movement that permanently altered the accepted understanding of alcoholism and addiction.

Widely known today as Alcoholics Anonymous, the program elevated the perception of addiction from a moral deficiency or weakness of character to an actual medical disease with pathology similar to tuberculosis or diabetes. Attempting once again to redefine addiction, the recovery sutras are intended to shift addiction from the disease model to a matrix of conditions best remedied through a wellness model and the healing properties of yoga.

The current model of Western medicine is centered upon a disease-based paradigm. Its chief strategy is to diminish, eliminate or mask diseases and their symptoms with the help of drugs and surgery.

Yoga is less concerned with treating disease and instead focused on wellness, specifically assisting individuals in realizing their goals and improving the quality of their lives. The ever-evolving practice of yoga has been defined as, “the ability to do something tomorrow that we can not do today.”

Developing vision

There are as many goals for a yoga practice as there are practitioners of it. A practicing Hindu’s highest goal may be union with God. For someone suffering from arthritis, running a marathon might be the ultimate aspiration.

An alcoholic or addict could focus on staying sober one day at a time, while his co-dependent wife’s aim might be to focus on something outside of her husband’s addiction.

Also Read>>> My Husband is Yells at Me

Whatever the goal, it is important to have individual clarity about the things we value and desire so we can plan for and attract them into our lives.

Also Read>>> My Wife Yells at Me

One of yoga’s essential tools for establishing goals, clarifying values and healing the individual is bhavana, or visualization. According to Sutra 1:20, the practice of smriti samadhi, or remembering and visualizing our goals, creates an abundance of faith and confidence called sraddha.

The more vividly and consistently we see ourselves attaining our aims, the more energy we generate to overcome obstacles and persevere. It is unlikely we will achieve something we aren’t able to imagine. Beyond nature, everything in the world that exists, each building, road, movie or book originated as somebody’s visualization.

The power of clarity

For the twenty years that I have been using yoga to coach individuals, I never cease to marvel at the ways visualization can be used to transform a person’s life. Its power is substantially magnified when the bhavana, or concentration of the visualization, is positive, concrete and specific.

Focusing on what we do want, instead of what we don’t want is paramount. Concentrating on what we want to create and increase in our lives is far more inspiring than what we wish to remove or reduce. Telling a restaurant server what not to bring us, no steak, no pizza and definitely no dessert, fails to clue them into what we are craving.

Addicts and their co-dependent counterparts often experience great difficulty expressing their goals and needs in positive terms. Their negative disposition frequently causes them to focus upon what they do not like, what they do not want or what is not working for them. This pattern is self-generating and ultimately produces negative feelings within their relationships. A downward spiral ensues and life becomes more difficult.

It is important to have a concrete goal instead of an abstract one. Many people tend to describe their aims in intangible terms like “be more present,” “live in the moment,” “have more energy,” etc. Yet they are unaware of the behaviors and actions these words encompass. For those in recovery, indulgence in chronic abstractness can be an obstacle to long-term sobriety and lasting joy.

I have observed many recovering addicts and yoga teachers speak for years about being grounded, centered and balanced, without taking the essence of these words to a level of observable conditions and behaviors.

As popular as abstractions may be, they are undigested notions masquerading as achievable aims. It is impossible to achieve a concept, so ensure your ambition has well-defined and measurable qualities.

Specific and precise visualizations are more likely to evoke powerful emotions and fuel our actions. Deciding we want to be serene, present and free lacks the excitement of visualizing ourselves doing an hour of yoga beneath Chennai’s morning sun, sipping on a frothy latte in a Florentine café or standing before a tiger on a wildlife reserve in India.

The more specifically we can envision our goals, the more capable we become in successfully planning for and charting our progress.

Born to be happy

Visualization is actually an inherent ability all human beings possess. Ask any healthy eight-year-old child what they want to be when they grow up, and their answer will be positive, concrete, specific and highly enthusiastic.

Just as asana helps us reclaim our original stamina and flexibility with guidance and practice, we can relearn the art of visualization to create a happier tomorrow. Choosing, focusing and sustaining attention on a specific object, or citta vritti nirodha, is the very definition of yoga found in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

Check Out>>> Life Beyond Addiction Programs by Tomy Rosen

Freedom from Addiction: To Depart

Whether it comes naturally or as the result of practice, the more positively, concretely and specifically we envision the conditions we desire—the closer we come to actually attaining these things.

Addiction is less likely to take root in a life that looks exactly like the one we envisioned for ourselves.

As a powerful tool for increasing and sustaining our vitality and joy, visualization can play an important role in our recovery by moving us towards our own lovable future. I can hardly wait.