astanga siva cakras and caturaṅga – what about the h

If you are a practitioner of the style of yoga populariZed by Pattabhi Jois, do you practiCe ashtanga or astanga? Or, like me in my early yoga days, do you simply wonder why sometimes it’s spelt one way and sometimes the other? If your yogic style is oriented more towards tantric influences, do you work with your cakras or your chakras? If you are a devotionally inclined yogi, do your offer your bhakti to Shiva and Vishnu, or Siva and Visnu?

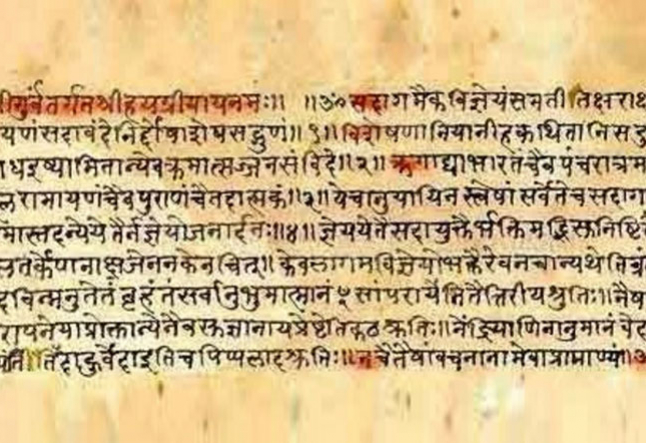

You might be forgiven for thinking that the letter ‘h’ in Sanskrit words is somewhat optional, but Sanskrit is an almost mathematically precise language and rarely that lax! And when we transliterate Sanskrit words into a western alphabet, we run into the challenge of using our 26 letters (or a few more or less, depending on the western language in question) to represent the 50 or so letters of the Sanskrit alphabet.

Why have one s when you can have three?

Sanskrit has three sibilant sounds: in other words, three ways of dealing with the letter we show as ‘s’. Conventionally, at least in these days of sophisticated word processing, these are shown in western script as s, ś and ṣ.

The first of them – s – is pronounced exactly as we would pronounce the first letter of the word ‘sock’. The other two are both, broadly speaking, pronounced as we would pronounce the ‘sh’ in ‘shock’. If we want to be real Sanskrit purists (aka geeks), we should sound the ś with our tongue forward in the mouth, and the ṣ with the tongue turned back so that it lightly touches the roof of the mouth.

Try it now and see if you notice the difference. Or how about the posture name that gives us all three letters in consecutive syllables – śīrṣāsana, the headstand… perhaps even try saying it while practising śīrṣāsana!

Aṣṭāṅga and Śiva

The Sanskrit word for eight is aṣṭau, which is pronounced ‘ashtow’ rather than ‘ashtoe’. When we combine that with aṅga, or limb, we end up with aṣṭāṅga, rather than ‘ashtanga’. The bhakti yogis, on the other hand, get the second s – ś – in the name of Śiva, but the third s – ṣ – in Viṣṇu. Confused? You’re not alone. If I’m honest, I still often have to stop and check which of the two I need to use in many words.

To be on the safe side, simply pronounce both ś and ṣ as an English ‘sh’, and hardly anyone will spot the difference. To use ‘sh’ in the written word, however, would simply be wrong. I’m fairly certain the world will keep turning if you do, but if you’re aiming to be get your Sanskrit right, you really need to drop the h.

And, just when you think you might be getting somewhere, I should probably point out that ‘S(h)iva’ rhymes with ‘liver’, even if ‘Sheeva’ is the way it is commonly pronounced. I know, that’s probably a whole other article, so we will leave it alone for now.

Why make life so difficult?

We might well ask, why do the conventional transliteration schemes not use ‘sh’, at least for one of them? The key to answering that was in our previous article – ‘Do you know how to pronounce haṭha?’, where we looked at the aspirated consonants in Sanskrit – like bh, th, and gh – which are pronounced by sounding the first letter with a short puff of air after it. (Try that holding your hand in front of your mouth and feel the air on your hand.)

So, even though Sanskrit does not have an aspirated ‘s’ sound, if we used ‘sh’ to represent either ś or ṣ, the likelihood is that some people would try to pronounce it as if it did: in other words by attempting to sound an ‘s’ with a puff of air after it – even though that is actually pretty tricky to do.

So what about cakras?

Or is it chakras? Here we run into the difficulty that Sanskrit does have an aspirated ‘c’ sound. In other words, ‘c’ and ‘ch’ represent different Sanskrit letters. The letter which we show as ‘c’ in a Sanskrit word is always pronounced as the ‘ch’ in ‘charity’ or ‘church’, never like the ‘c’ in ‘cat’ or ‘cascade’. If we want that sound, we use ‘k’. So, ‘cakra’ would never be pronounced ‘kakra’, but should always be pronounced ‘chakra’.

By the way, it’s definitely not ‘shakra’, but maybe don’t get me started on that today. We don’t need to insert the ‘h’: in fact to do so here would technically be incorrect, as we would then be using the aspirated ‘c’, not the ‘simple c’, and would have to puff the air out.

I am well aware that this might sound fussy, but, in the Sanskrit alphabet, inserting an h would change the word completely. Put simply, the Sanskrit alphabet is fussy. This isn’t surprising when you consider that the word ‘Sanskrit’ is generally translated as polished, perfect or refined, and that many say it is one of the most ‘perfect’ languages in terms of its structure.

Does all of this really matter?

Well, I guess it depends how true you really want to be to the ‘language of yoga’. Many authors take the not unreasonable view that it is easier for an audience not versed in the nuances of Sanskrit pronunciation to be given a word which looks like it should be pronounced – hence ‘ashtanga’, ‘Shiva’, and ‘chakra’ are all in common use.

And, before the days of word processing, even academic books and articles did use ‘sh’, and sometimes ‘zh’, for ś and ṣ, for the simple reason that they had no way of showing the diacritical marks – in the same way that they used ‘aa’ instead of ‘ā’ to indicate a long vowel sound.

There are no hard and fast ‘rules’ about transliterating Sanskrit into western script. However, as a result of modern word processing systems, a fairly established set of conventions has grown up and, now that most of us have computers which allow us to follow those conventions, perhaps there is less excuse for not ‘getting it right’. Bear in mind that what can often seem a minor difference can change the meaning of a word radically.

Some years ago, a student who knew some Sanskrit quizzed me about the squatting posture known as mālāsana – the garland or necklace. For years, she said, she had been worried about the name of that posture. Why?

Because she knew enough Sanskrit to know that mala (as opposed to māla) meant ‘filth’ (or even ‘faeces’)… and every time she squatted into the posture, she wondered whether she was really doing the ‘crapping posture’. Food for thought next time you have an idle moment in caturaṅga – which, you now know, has nothing to do with cats…

This article is the fourth in a series of articles considering Sanskrit faux pas. Check out the first three:

It’s not the crow!

Vīrabhadra doesn’t mean warrior

Do you know how to pronounce haṭha?